Owing to their complexity and strategic relevance, mergers, acquisitions, and carve-outs present some of the greatest challenges facing companies. How can CFOs successfully accompany the transition and transformation phase?

Companies operate in an increasingly competitive environment and can sustainably enhance their value through inorganic changes — the purchase or sale of parts of companies. As their position entails a key role in these activities, CFOs bear co-responsibility for preparing and executing the transaction and securing the financial synergies intended as a result of the transaction. Depending on the scope of the transaction, an organizational, procedural, and digital transformation of the company is required. CFOs not only ensure that their own finance organizations are transformed and digitalized, but support the other organizational units during their transformations pursuant to inorganic transactions.

What is the relevance of corporate transactions?

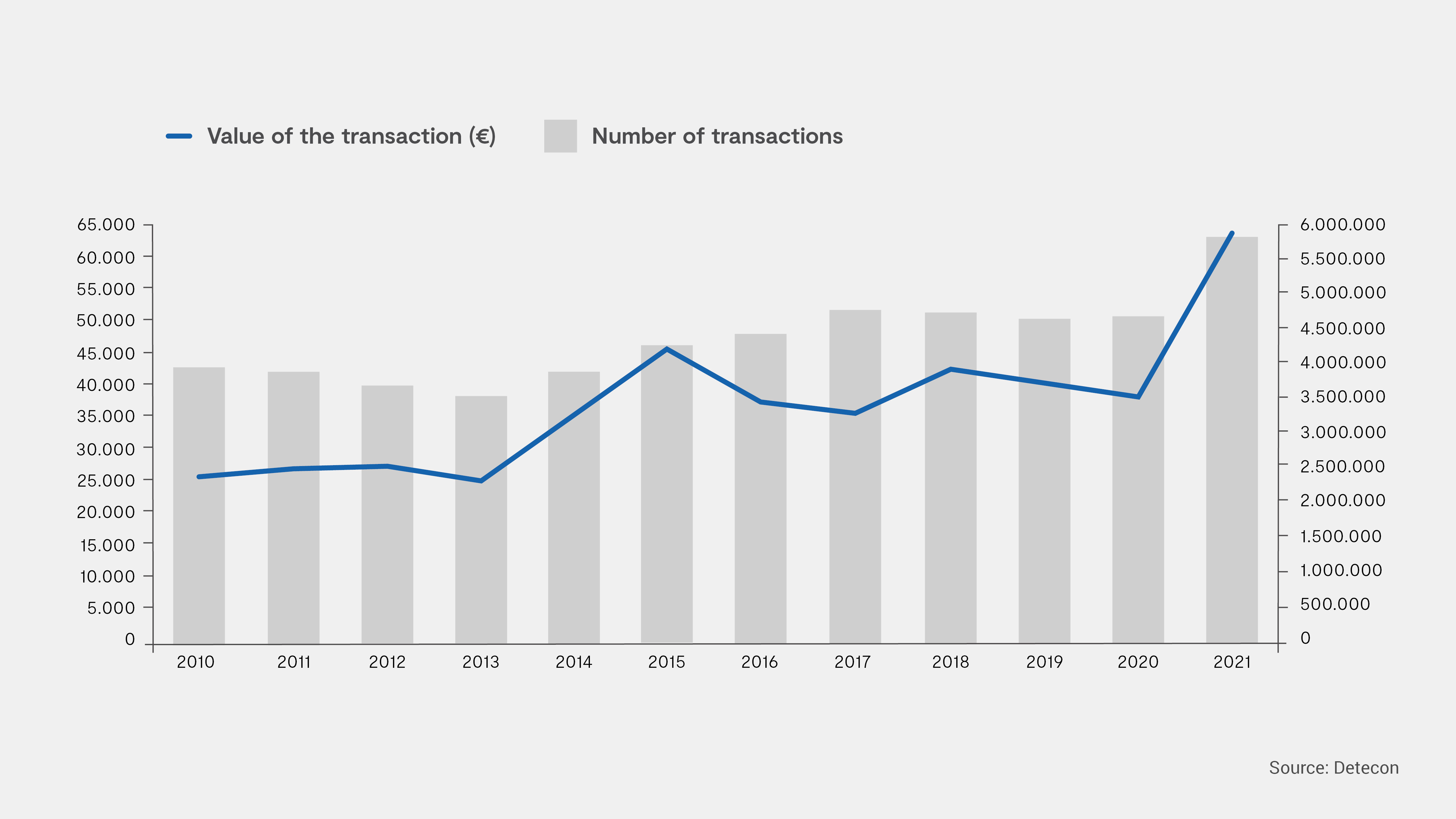

2021 was a record year for M&A transactions. Following a decline in these activities in 2020, both the number of transactions and the total value of all transactions peaked in 2021, accompanied by rising valuations and financing. The combination of general economic growth, rising market capitalization, low interest rates, and huge numbers of available transaction objects led to a significant global increase in M&A transactions (see Figure 1).

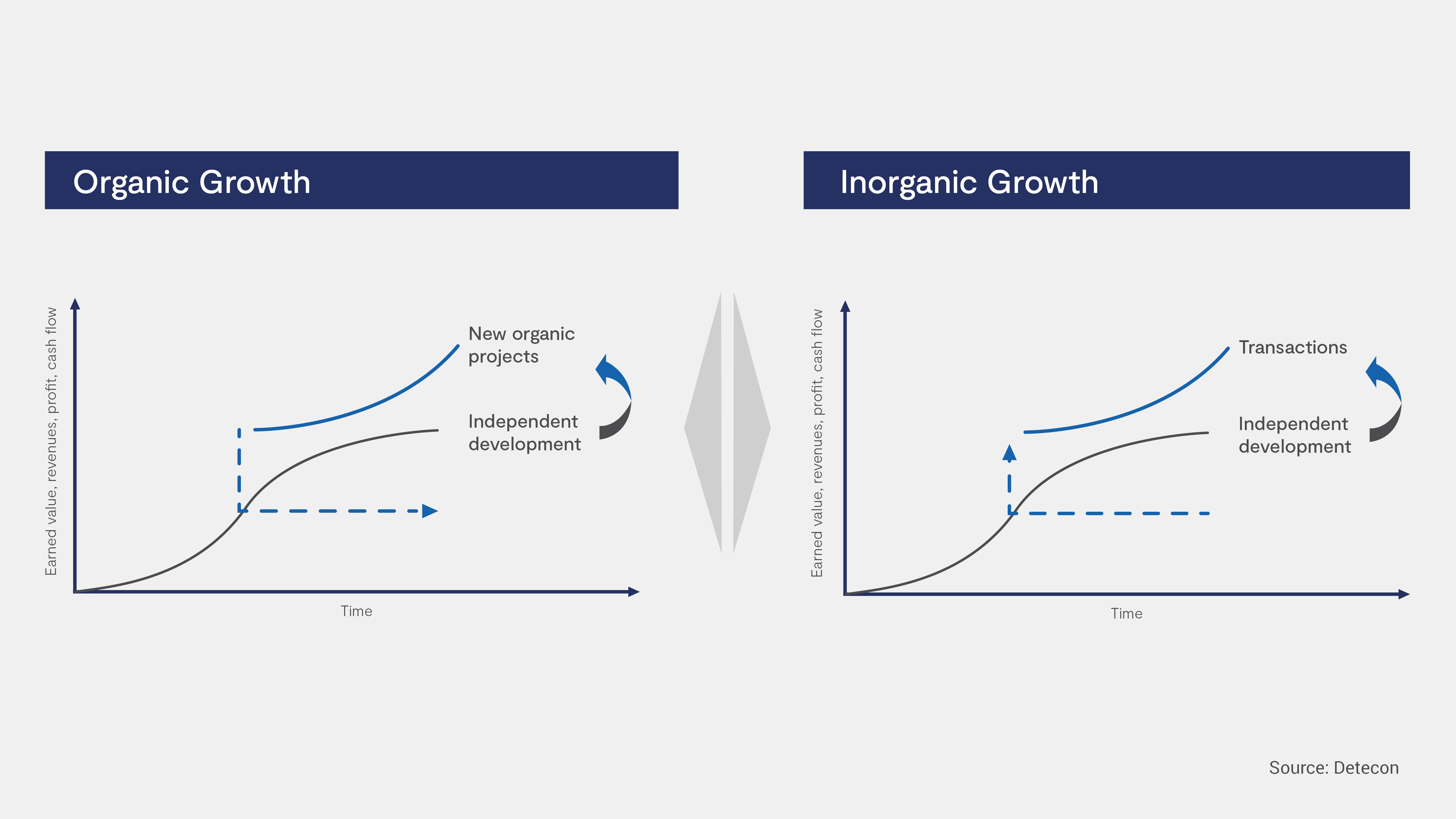

Strategically, companies follow a continuous path aimed at increasing shareholder value and sustainable competitive advantages. Depending on their strategy, companies can increase their corporate value by growing organically or inorganically or even combining the two growth options.

Organic growth is achieved by the conduct of new, internal investments or projects — for example, by investing in the development of new products and services, the optimization and rationalization of resources, and measures to increase efficiency. The primary motivation behind organic growth is to realize solid, sustainable, and long-term growth (see Figure 2).

The two most important strategic goals in pursuing inorganic growth are usually either the achievement of horizontal scaling advantages such as efficiency gains or of vertical economies of scope (e.g., cash flow optimization) (see Figure 2). Transactions with a focus on economies of scale or gaining a lead through large volumes pursue the goal of profiting from consolidations — for example, improvement of the cost position or achievement of medium-term optimization of earnings and cash flow.

This type of transaction is typically driven more strongly by CFOs and their organizations. On the other hand, transactions focusing on economies of scope or securing an advantage from the exploitation of synergies pursue the main objective of increasing the company’s efficiency for strategic reasons. In some cases, companies also pursue the goals of rapid growth (e.g., by entering new markets or achieving growth in fast-growing market segments) or of strengthening innovation (by developing new products or services, for instance) along with cost advantages. The transaction volume here is generally smaller than for transactions focused on economies of scale; however, such actions are more expensive because of their complexity. CFOs and their staffs should be deeply involved from the beginning, especially during the target screening and due diligence phases.

If a company decides to sell a subsidiary, the transaction is typically known as a carve-out. This type of transaction can increase the corporate value if both the parent company and the separated subsidiary operate as separate entities. The motivation behind a carve-out is the stabilization or focus on the businesses that have not been sold and the optimization of cash flow by utilizing the proceeds of the sale to make other acquisitions or reduce debt.

M&As and carve-outs are complex, incur transaction costs, and in most cases can present various challenges. The finance department has the special task of minimizing and preventing the associated risks:

-

Unexpectedly high transaction costs (basic costs as well as costs for transaction consulting)

-

Dis-synergies such as loss of revenues or difficulties in carrying over service agreements

-

Inefficient cost structures in the parent company after the transaction — for example, sticky costs from excess personnel in shared service centers

-

Stress and resources needed within the organization — specialists, management, and others.

CFOs play an essential role in the preparation and execution of transactions and ultimately in the successful completion of transactions. Forty-three percent of the CFOs surveyed in a study on the evolution of their role in the company state that their responsibility for transactions or post-merger integrations is on the rise.

The key role of CFOs to define guidelines for the transaction and identify potential targets is essential right from the early stages before a transaction starts and is not limited to the execution of the transaction. Furthermore, the CFOs should be in a position to ask difficult and critical questions before an agreement is reached on a transaction.

What role do CFOs play within corporate transactions?

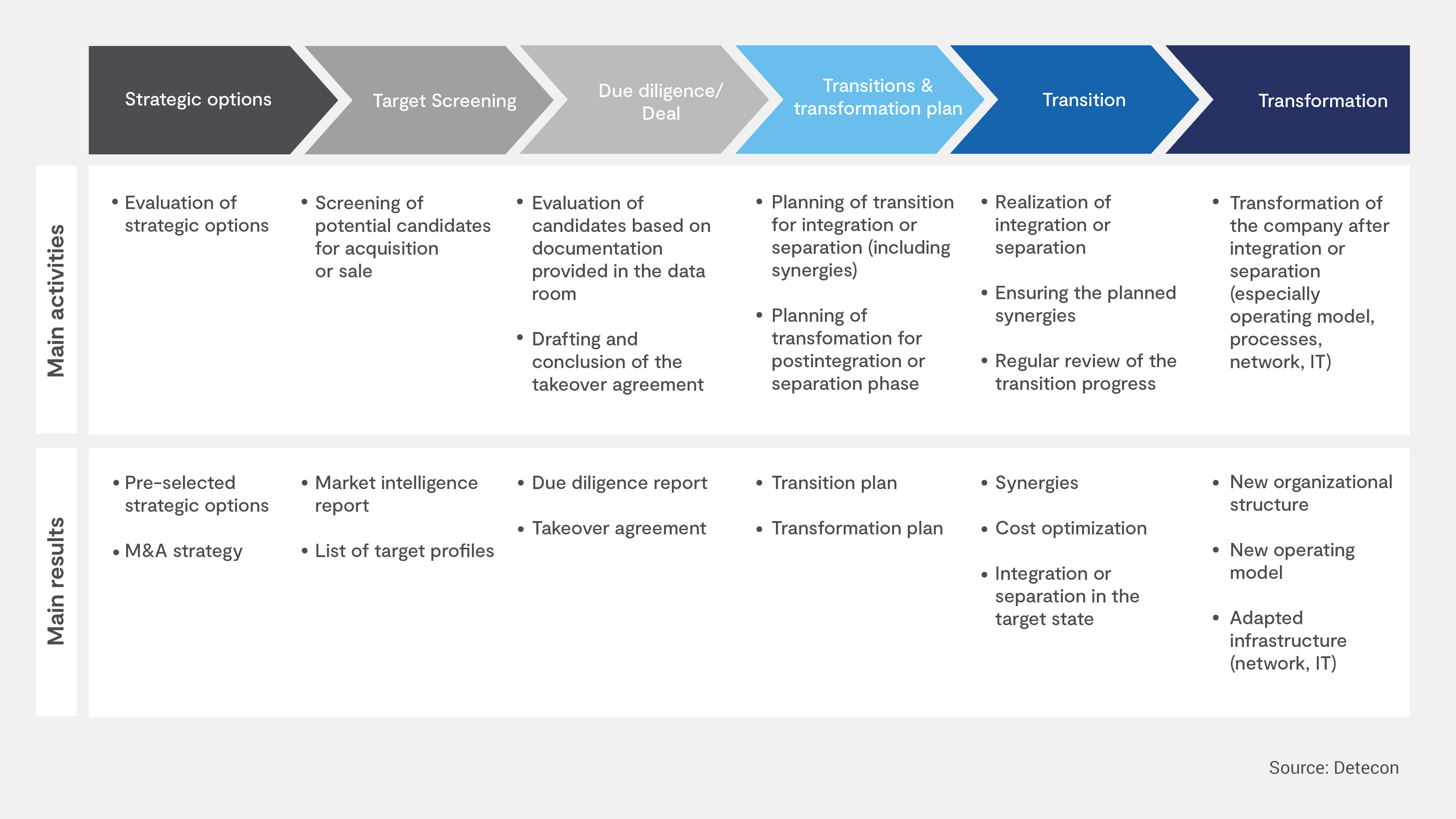

The classic transaction process breaks down into six phases (see Figure 3).

But what do CFOs require if they are to turn a transaction into a success? CFOs and their organizations should be decisively involved during all phases of the transaction process. As they are in charge of corporate finances, the CFOs share responsibility with CEOs for a successful transaction.

CFOs have the opportunity to join CEOs in a strategic position. Approximately 41 percent of all CFOs report that their interactions with the CEOs during transactions have steadily increased. Within the framework of the strategic early stages of a transaction, CFOs are responsible both for formulating guidelines for the identification of potential candidates for acquisition or sale and for assessing the profitability and risks of potential candidates. This leads to CFOs being in charge of the preparation of a comprehensive business case. Once the company has reached the transaction stage, CFOs act as guides of the transaction agreement so that the company obtains the best possible transaction terms and realizes cost efficiencies and other financial goals.

Even after the early strategic phases, however, CFOs are also responsible for the smooth and efficient execution of the transaction in the sense of integration of an acquisition into the company’s own operations or the carve-out of a subsidiary. The transaction itself realizes the actual value that becomes possible when its execution is fast and free of friction. The fast and effective execution of the transaction allows CFOs and the involved companies to refocus quickly on the remaining business.

Following the due diligence phase and the closing of the deal, CFOs should stand out during the transition — i.e., the integration or separation — by securing the planned financial synergies that include in particular classic synergy effects such as greater efficiencies or cost reductions. In the subsequent transformation phase, CFOs should lead the business in regarding integrations or carve-outs as opportunities for broader organizational and process transformations while also ensuring business continuity and the market position of the involved companies.

For example, a CFO may facilitate discussion on building a shared service center or streamlining IT systems. The important element here is the definition by the CFO of appropriate metrics for measuring success at an early stage and the monitoring of their development.

How can CFOs successfully accompany the transition and transformation phase?

Detecon, a reliable companion during the transition and transformation phase, regards three factors as essential for successful realization of the transaction from the CFO’s point of view:

-

Financial synergy effects during transition phase:

The key driver of a transaction is the realization of intended financial synergy effects that are expected to result from the transaction. They include especially classic synergy effects such as revenue increases, efficiency gains and cost savings resulting, for example, from product portfolio optimization, more favorable access to new capital, access to new market and customer segments, optimized capital allocation within the company, lower taxation, and a reduction in overall risk.

Estimating the scale of the synergy effects is often a difficult task and highly dependent on the objective of the acquisition or carve-out as well as on the buyer or seller. In most cases, there is a lack of adequate transparency concerning the company that will be integrated or separated until the transition phase begins. This is true both of various departments of the company that will be integrated or separated (such as the IT systems), but includes as well their dependencies on the processes in the target company. Such factors mean it is important for financial synergies to be planned and realized iteratively as early as possible. Financial synergies during a transaction are not calculated only once; they are tracked regularly and systematically. The cost of a transaction along with its medium to long-term cost savings as the outcome of a transaction is another important component of tracking.

-

It includes, for one, the costs of the transaction itself. In the last 20 years, advances in information technology have been so great that ERM systems, for example, integrate various business activities so tightly that a decoupling becomes very costly.

-

For another, CFOs should also focus on potential sticky costs. Sticky costs in this sense refer to costs that continue to be incurred to the same extent despite separation and can include such costs as overheads for the group-wide finance or personnel divisions. CFOs should always allocate cost-reduction targets to specific initiatives such as overhead within a specific time.

-

Business support during transformation phase:

In addition to securing financial synergies, CFOs also accompany the transformation. After completion of an integration or separation, both organization and processes are commonly optimized. CFOs are responsible for providing guidance to business leaders on the financial opportunities of organizational and process changes as well as a realistic view of costs. Besides new operating models, there are issues revolving around the establishment of shared service centers and the consolidation of IT systems.

Since transformation initiatives are realized alongside business operations during the transformation phase, it is important that this takes place as quietly as possible vis-à-vis customers and that failures on both sides be avoided. CFOs assist in the prioritization of initiatives for each business function, taking into account the operating business, so as to ensure the smooth course of business. The negotiation and agreement of temporary management systems or transitional service agreements with the transferring company may be necessary. The latter are intended to ensure the functionality of the separated company during the transition and transformation phase.

-

Standardization/automation through digitalization during transformation phase:

Within the transformation phase, CFOs should also play an active role in supporting and driving forward the digitalization of the finance organization, processes, and systems. Digital transformation is a means of generating efficiencies through standardization and automation. The strategic direction of each transformation phase must be determined top-down by the CFO, however.

Moreover, the entire IT landscape should be carefully reviewed after a transaction as it usually comprises multiple ERP systems — for example, SAP and non-SAP — and is generally often complex and decentralized. For the most part, it consists of systems for various business units, positions, or regions. The most important challenges are the minimization of business disruption during the transaction and increasing the efficiency of the organization with system support.

Ensuring seamless transitions determines the success or failure of newly acquired or merged companies

In one study, 94 percent of respondents said at least one of their company’s initiatives with another company had failed because of the mismatch of the ERP systems. At a time when the number of mergers and acquisitions is at its highest level since 1995, ensuring seamless transitions can mean the difference between success and failure for newly acquired or merged companies.

Detecon has supported numerous clients in centralizing and digitally transforming the CFO purview. For example, Central Finance for SAP S/4 Hana is an accelerator for integrations and carve-outs because it allows companies to continue to operate in legacy systems.