"A smart transportation system does not need a transparent citizen". This is one of the theses which was derived within the Detecon Smart Mobility Study. But what does this look like from the point of view of the various participants? In this article, we discuss the thesis from the perspective of the state, mobility service providers, and citizens. How far must and may the collection and processing of data go? How much and what kind of data is needed for a smart transportation system and what does data protection say about it? By including critical success factors and on the basis of existing use cases, current as well as future challenges for stakeholders are discussed. Finally, we conclude that a Germany-wide overall architecture of the transport system represents a target picture that is sufficient for all stakeholders.

Mobility and the way we travel will change significantly in the future and adapt to the needs of travelers. It is no longer just a matter of getting to the destination quickly, but of being able to devote the time spent on the road to other activities, such as learning, working and reading. In other words, it's about covering a distance with any combination of different means of transport, and doing so as comfortably, cost-effectively and quickly as possible. This requires the digitalization and networking of all means of transportation to create a unified and intelligent overall system, the so-called "smart transportation system." It focuses on the collection, transmission, processing and use of traffic-related data with the aim of organizing, informing and directing traffic using information and communication technologies.

This smart transportation system needs data to provide its services to the fullest extent. However, data protectionists can breathe a sigh of relief: turning travelers into "transparent citizens" is not a necessity for making the mobility ecosystem smart. Indeed, the primary focus is on traffic data, such as transportation movement data, incidents, and historical data, as well as analysis of aggregated and anonymized traveler movement data. We want to address smart use cases within the city and therefore explicitly use the word "citizen". We define a "glass citizen" as citizens* who have to disclose any data, e.g. location, individual identifiers for (motion) profiling, contact data, camera and microphone, in order to use services, in this case mobility services.

Since a large amount of data is already available, it will not be absolutely necessary to collect even more data. In the future, it will be more a matter of using and evaluating this data correctly (article on the topic: "The data in the haystack") in order to constantly optimize and improve the mobility ecosystem (through new demand-oriented stations, transfer points, bus routes, etc.).

Too many cooks spoil the broth?

The first step is to consider the stakeholders under whose influence the intelligent transportation system is maturing. In this context, three key players have been identified in the study: the state, profit-oriented mobility operators, and the (transparent?) citizen.

The state as guardian and guide

The Federal Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure (BMVI) is significantly committed to making transport more intelligent. The implementation of EU Directive 2010/40/EU "on the framework for the deployment of intelligent transport systems in road transport and for their interfaces with other modes of transport" was implemented in the Federal Republic by the "Intelligent Transport System Act (IVS-G)" in mid-2013. This law defines the priority areas of application, which include traffic safety, optimization of use, continuity as well as the interfaces to different modes of transport. It should be emphasized here that federal legislation is required to collect, process or use personal data.

The Federal Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure is also responsible for the "National Road Action Plan", as part of which a mobility data marketplace has been set up. Here, data providers can make traffic-relevant online data available to so-called data consumers. Based on the data available on the platform, a number of use cases have been created, some of which are currently in live operation. Among others, the city of Frankfurt a.M. and the navigation service TomTom cooperate to manage traffic in the Frankfurt metropolitan region as efficiently as possible. TomTom provides processed floating car data, which is made available to road users by the Integrated Traffic Control Center (IGLZ). The state thus assumes the role of guardian and driver. It ensures that the rights of its citizens have top priority and at the same time defines the framework for a networked exchange between all ecosystem participants.

Usage profiles and new business cases for the mobility service provider

The fundamental interest in using historical and live data to positively influence traffic patterns is also on the agenda of mobility service providers and OEMs. Nonetheless, we would like to point out that the motivation to collect, process and use data is primarily monetarily driven. Usage data of any kind can be analyzed to get to know end customers better. This is done, for example, in the form of non-personalized usage profiles. By taking these into account, it is possible on the one hand for the stakeholder to minimize the risk of accidents. On the other hand, products are optimized according to usage behavior or the possibilities for new business cases are discussed, which will allow more third parties, such as insurance companies, to enter the ecosystem in the future.

Fast, efficient and reliable - that's how citizens want to get where they want to go

Last but not least, we have the citizen as probably the most important stakeholder in the mobility ecosystem. It is the citizen who plays a key role in ensuring that the services offered by mobility providers are successful. If the citizen does not accept the services or the technology as such, the smart mobility concept will also fail. Everything stands and falls with the user. For the citizen, the focus is on getting to a destination quickly, efficiently and with comparatively little effort (in terms of financial and transfer effort). For example, a traveler would be more likely to use a car if he could cover the planned route faster, more reliably and more cost-effectively.

Therefore, a better and more reliable coordination of the means of transport with each other and with the current location of the citizen is desirable. For this, of course, the citizen must disclose data about himself: location, start and destination of the trip, and possibly payment information to be able to buy necessary reservations/tickets before the start of the trip.

Data protection must not be ignored here. Since the introduction of the GDPR last year, the topic is receiving more and more attention and is gaining in importance.

Call for data protection

All IoT devices constantly collect data, which is often subject to the BDSG and the DSGVO. In addition, the networking of these IoT devices via the Internet and the general connectivity creates a potential point of attack for security attacks, which is why the topics of data protection and data security also play a major role in the area of smart mobility. The overriding goal here is to ensure the transparency, security and privacy of personal data vis-à-vis the user as prescribed by data protection laws. For example, data must be anonymized and viewed collectively to avoid the risk of creating individual movement patterns. Likewise, technologies to prevent cyber security attacks must be implemented within the mobility system.

Since the overall smart mobility system is made up of several stakeholders, the idea of data protection must be (re)awakened in everyone involved and the relevance must be known to everyone. Otherwise, there is a risk of data misuse and cyber attacks. It is not enough for data protection measures to be implemented and used by just one provider, because as we know, a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. If the smart transportation system is to be successfully integrated into cities in the future, companies and cities must increasingly address the issue of data protection and find solutions to implement this in a targeted manner. Otherwise, violations of laws and guidelines could result in sanctions and financial damage.

„Data is the new oil“

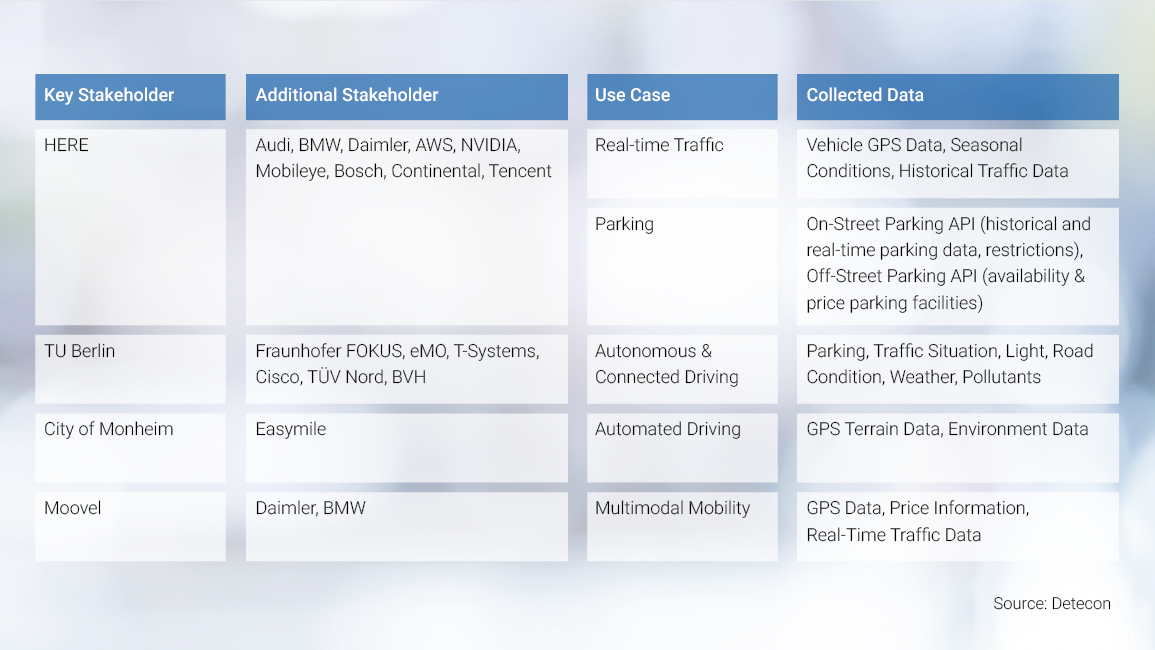

What does data handling currently look like in a smart transportation system? In general, "data is the new oil", now and in the future. Therefore, the overriding question is at what "price" the citizen can enjoy optimized traffic flows or intermodal mobility. In the medium term, it will be possible to map this via autonomous vehicles. GPS, speed, braking behavior, fuel consumption, sonar, lidar and cameras alone are used to collect and evaluate billions of data records in order to constantly improve the neural networks and algorithms and thus ensure the most accident-free, economical and autonomous journey possible. A closer look reveals that the data collected is by no means stored solely by automotive manufacturers. Suppliers and third-party providers to the automotive industry contribute a large number of the sensors and software installed externally to vehicle construction and thus also benefit from the new oil. HERE, the provider of an online geodata service as well as navigation software, can be used to illustrate the scenario. The data collected by HERE comes from smartphones, vehicle and road sensors, and navigation systems, for example. Partners and/or shareholders of HERE include Audi, BMW, Daimler, AWS, NVIDIA, Mobileye, Bosch, Continental, and the Chinese tech giant Tencent, all of which are likely to have an increased interest in the aggregated data.

According to the stakeholders identified, the view toward the state is also important here. Public research institutions such as the Technical University of Berlin in cooperation with partners from industry have recently implemented an autonomous test field in downtown Berlin. In order to reach the final stage of autonomous driving, Level 5 - where there are only passengers without a driving task - information from external sensors is required in addition to the vehicle sensors, which, among other things, records the behavior of all road users. Here, too, the goal was to ensure an accident-free flow of traffic.

The city of Monheim in North Rhine-Westphalia is a pioneer in autonomous public transport. Mobility experts have been watching the implementation of the small town's autonomous strategy with interest for several years. A test field with autonomously driving (electric) buses is being built here. Detecon's feasibility study helps to take a medium- and long-term view and to avoid isolated solutions in planning. Instead, as the complexity of the intelligent transportation system increases, the focus should be on centralized smart city platforms.

The table provides a good overview of the type of data that is officially collected for the use cases described. What is striking here is that it is primarily the GPS data of citizens that is processed in order to make traffic smarter. However, this rather "personal" information does not have to be directly linkable to the user in order to draw relevant conclusions for the respective use cases. However, it is doubtful whether this will meet with the approval of the key stakeholders.

What is missing is a comprehensive architecture for entire Germany

So there are already individual smaller use cases that take up the smart mobility idea and implement it in part. However, these are still isolated solutions at the moment. The focus must therefore be on developing an overall architecture for the whole of Germany. In the future, all services within smart mobility should be accessible on one platform. In addition to relevant analysis platforms, this platform will also contain and make available the respective services and technical characteristics of smart transportation networks. To achieve this goal, however, standards must be defined and established that providers can draw on when developing hardware or software. This ultimately ensures that all providers in the mobility ecosystem "speak the same language." It is also easier to integrate different solutions from different providers if the same standards are used.

Networking various providers via a platform also makes it possible to view the services offered in a consolidated manner and ultimately to use and pay for them via a single app, for example. The city of Monheim is taking a first step in the direction of an overall architecture with its Monheim Pass. In the future, residents will be able to use and pay for municipal services with this pass.

What does the future hold with a smart transportation system?

In the future, new technologies such as AI and big data will help to tailor the mobility ecosystem even more precisely to the needs of individual citizens. Conversely, this means that data protection will soon have to play an even more important role due to the increasing amount of data available and to be processed. At the same time, AI and Big Data are not critical to data protection per se. However, it must be ensured that all parties involved implement and use necessary protective measures. To further mitigate the "human" risk, more research needs to be done in the area of technological safeguards. For example, IOTA and blockchain will certainly play a significant role in the future when it comes to IoT security and secure data transmission. However, citizens must understand and accept the functionalities of smart mobility. It must become clear what the individual benefits of a smart transportation system are, otherwise this will meet with rejection and mistrust from citizens.

We were able to confirm the hypothesis that emerged from our survey, "a smart transportation system does not need a transparent citizen," assuming that the collection of personalized data is desirable, at least on the part of mobility service providers. However, in order to make mobility as efficient and precise as possible in the future, the citizen's data only plays a secondary role. For the time being, the only important thing here is to bundle the anonymized data from the mobility ecosystem and make it available to a traffic monitoring system for analysis.

Depending on the use case, the data requirements may expand and additional data sources must be considered and included in the analysis. The larger and more complex the "smart traffic system" use case becomes in the future, the greater the need for additional data sources for analysis. In our opinion, however, it is not necessary for the data to be linked to citizens.