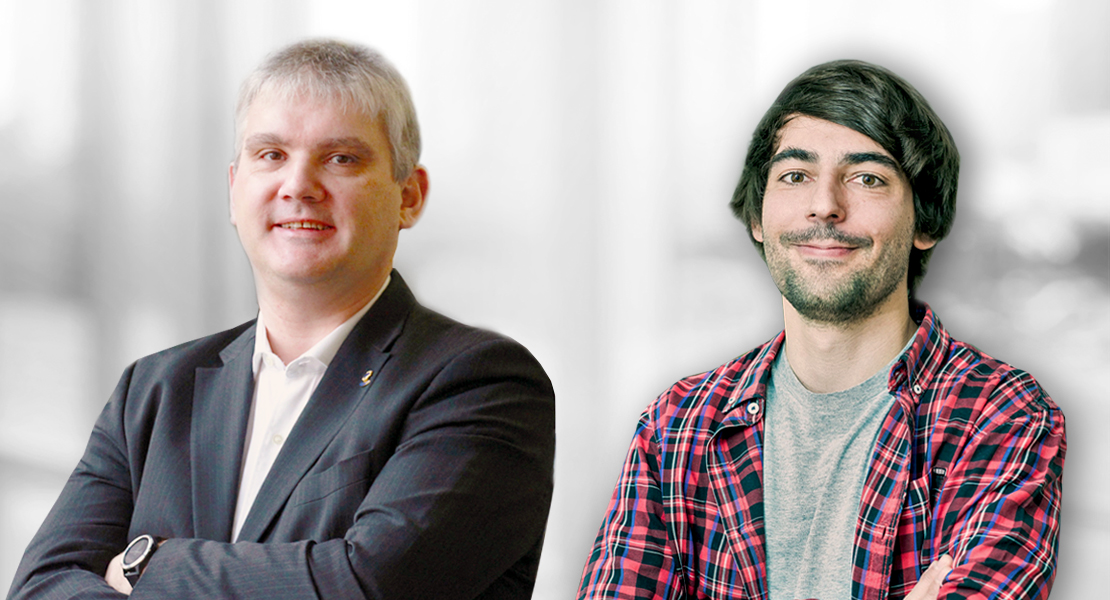

How can sustainability be reconciled with the transformation of industries? Professor Rupert J. Baumgartner and Josef-Peter Schöggl, PhD, from the Institute for Systems Science, Innovation and Sustainability Research of the University of Graz argue for more radical paths in product development and the principle of the sustainable circular economy.

The discussions about environmental sustainability have clearly accelerated in recent years. How do you view the development in industry in particular? Have there been missed opportunities in this respect, or does the adaptation adequately address the real challenges of the necessary transformation?

Rupert Baumgartner: The industrial sector was a long time in taking the issue seriously. It has been clear since the 1990s that we must do something about resource consumption and emissions. A planned transformation is required, and companies have a special role to play. Occasionally, the identification of a suitable business case led a wallflower existence. The fossil fuel and steel industries long resisted emission trading, in no small part because of the technical specifics. Many European companies are feeling high regulatory pressure. For instance, the idea behind the circular economy model is non-negotiable. Then there is public pressure from people and initiatives such as Greta Thunberg and Fridays for Future.

As I see it, companies should recognize that strategic efforts to achieve sustainability will lead to numerous opportunities. Understanding sustainability principles in the company’s core business can drive business ideas and innovation forward. Interest is steadily rising, although tremendous uncertainty also dominates. Then there is also the serious issue of greenwashing. Companies that are making honest efforts and thinking strategically will be the players who are most likely able to play a part in directing the transformations — and to their own advantage.

Josef-Peter Schöggl: We asked Austrian companies about specific approaches to sustainability management and their realization. About a quarter of them have incorporated sustainability topics such as ecological design, sustainable supply chain management, or recycling throughout their company. We also asked to what extent they were dealing with the issues in smaller pilot projects or were currently engaged in the realization of these measures.

About half of the companies have taken steps in this direction. Although two-thirds of Austrian companies have already defined a sustainability strategy, comprehensive changes in business processes and models oriented to a circular economy remain rare as of today. Most of the issues are driven by the aspects compliance and efficiency. Production and design questions such as increasing material or energy efficiency in production or closing internal material cycles along with the avoidance of toxic substances take priority.

At the World Economic Forum in 2020, Angela Merkel made the following statement: “This transformation basically means that in the next 30 years we must leave behind everything about the way of doing business and living our lives to which we have be-come accustomed during the industrial age ... and arrive at completely new forms of value creation that will of course still include industrial production and that will have been changed above all by digitalization.” What would you say about this quote?

Baumgartner: I like it because it describes the challenges. We must reinvent industry and business. We currently obtain more than 65 percent of the world’s energy from fossil sources. Over the next 30 years, human population will grow by the equivalent of another India and China. There are only two paths that will lead to a successful transformation: either the decoupling of resource consumption and environmental or climate pollution through new types of economic activities or radical degrowth. Personally, however, I do not see any way that radical degrowth on a democratic path can be achieved solely by our voluntarily giving up our current standard of living. The key challenge is decoupling — disengaging from fossil capital stock and reinventing industrial production.

There are sectors and circumstances specific to various countries where this is extraordinarily challenging. Look at Great Britain: a low level of production and a concentration of services result in a smaller carbon footprint here. But the calculation is dishonest because production has merely been outsourced. Cement, steel, and the like must first be reinvented. On the one hand, the transformation must succeed technologically; on the other hand, the business models and consumer perspective must be designed more innovatively. Between 2008 and 2018, total electricity consumption in Austria increased by more than 6 percent and will in the future grow even faster because of the unavoidable electrification, e.g., in the mobility sector. Looking strictly at the technology of the providers is insufficient; the efficiency on the consumer side must also be considered.

Rome was not built in a day. It is important to think and act step by step, isn’t it?

Baumgartner: That’s right. We find the so-called paradox perspective among the employees of companies. Knowing that transformation and radical change are needed now, but that they must nevertheless be embedded in the current framework. This means taking steps in the right direction immediately, yet not being able to solve everything directly. Paradox tolerance should be promoted in organizations — for example, by building up expertise.

You are the director of the “Christian Doppler Laboratory for Sustainable Product Management”. How can sustainability by design become a part of thinking about the business case? How can sustainable product management be established and properly implemented in digital products as well?

Baumgartner: In our research, we looked at the current state of product development processes from the perspective of sustainability and a circular economy. We were surprised at just how little strategic thought goes into the creation of product development processes. The design process often involves tweaking existing products rather than radically redesigning from scratch. Company management needs to become more involved and consider sustainability issues at an earlier stage during product development.

Schöggl: We found the same situation in another study with product developers, primarily from the European automotive industry, regarding the hurdles in sustainable product development. Besides the aspect of a lack of added value, strategic commitment was the greatest challenge. At the operational level, there is the question of tradeoffs, of a gain at one point involving a corresponding loss at another. This is not a trivial issue, especially for complex products. Ultimately, what can the designer really change?

Baumgartner: It’s fairly easy to put it in concrete terms in product development. To begin with, it is more important to know in what sustainable direction you want to go than for it to be quantifiable. Basic sustainability principles serve as a starting point for the stimulation of creative processes that can be triggered with a list of radical questions, for example. When it comes to the realization, all key decision-makers should be on board.

Can digitalization be assigned an important position in sustainable product design?

Baumgartner: We see enormous potential in this respect. Digital technologies can resolve the design paradox, i.e., confident decisions about new product features, materials, or technologies can be made without quantifiable detailed knowledge. If, for example, the focus is on similar applications, important information can be incorporated into the new development process at an early stage. Data sources for the design process can be obtained in the form of digital twins or digital product passports. Moreover, digital technologies offer better simulation of the use phase.

There is currently a lot of hype about e-mobility in Europe. You are collaborating with companies on a digital product passport for batteries. How does that contribute to sustainability?

Baumgartner: The fundamental idea is to collect in the product passport all the information from a sustainability perspective that is important for decisions along the product life cycle. Ideally, the product passport contains information about the origin of the product and raw material, what materials and what companies are and were involved. Use cases can be second life or end-of-life as well as others. Even if a battery can no longer meet the requirements for use in a car, it may still be good enough to use as stationary power storage. The cell chemistry in the product is an extremely important aspect for the recycling processes. At the moment, we have conceptually defined what information would ideally be contained in the passport. Now the question is how these information gaps can be closed. Supply chain players do not volunteer to share all the required information.

You have been working intensively on the aspect of the “circular economy.” Among other facets, this concept focuses on repair as an important step for the longer use or the reuse of assets. A skill that has become almost a lost art in Central Europe. What pragmatic steps towards a more sustainable circular economy might come into question?

Baumgartner: This is an important question because for many, circular economy still means primarily recycling and better waste management. But it is essential to stop creating so much waste in the first place. The longer use and repair of products play a very important role in this sense. Yet there is a huge discrepancy between what theoretically should be done and what is actually being done. Eliminating this dichotomy will require legal regulations, to start with. Second, we need business models that make the realization of these advanced strategies for a circular economy feasible. The combination of (legal) framework conditions and entrepreneurial creativity will open the door to increased sustainability that also makes economic sense.

What do companies believe will become increasingly important in the future?

Baumgartner: As the shortage of personnel and skilled workers continues to worsen, companies must not be negligent when it comes to internal personnel development; they will have to assert themselves more and more when it comes to sustainability issues so that they remain attractive to young, creative and bright minds.

Thank you for the interview!