Data as lifelines in the complex mobility ecosystem

There can be no dispute that the mobility sector is in the midst of upheaval. In the wake of digitalization and the demands on mobility of the future, the transformation of the industry into a sharing economy is these days viewed more as a social necessity than a potential scenario for the future. Paradigms such as mobility as a service (MaaS) and seamless mobility dominate the strategy meetings in more than just a few executive suites. The exact form that the ambitious transformation of the sector will eventually take, however, is still uncertain. Much is inevitably tied to the willingness to collaborate of numerous players in this interwoven ecosystem, many of whom are pursuing divergent goals. Parties with an interest in the movements of people include, for instance:

- Individuals/groups traveling for personal reasons

- Competing mobility service providers

- Operators of the (telecommunications) infrastructure

- Providers of mobility platforms and apps

- Manufacturers of transportation means

- Data suppliers outside the mobility sector such as card services

- Public institutions such as cities and airports

- Government

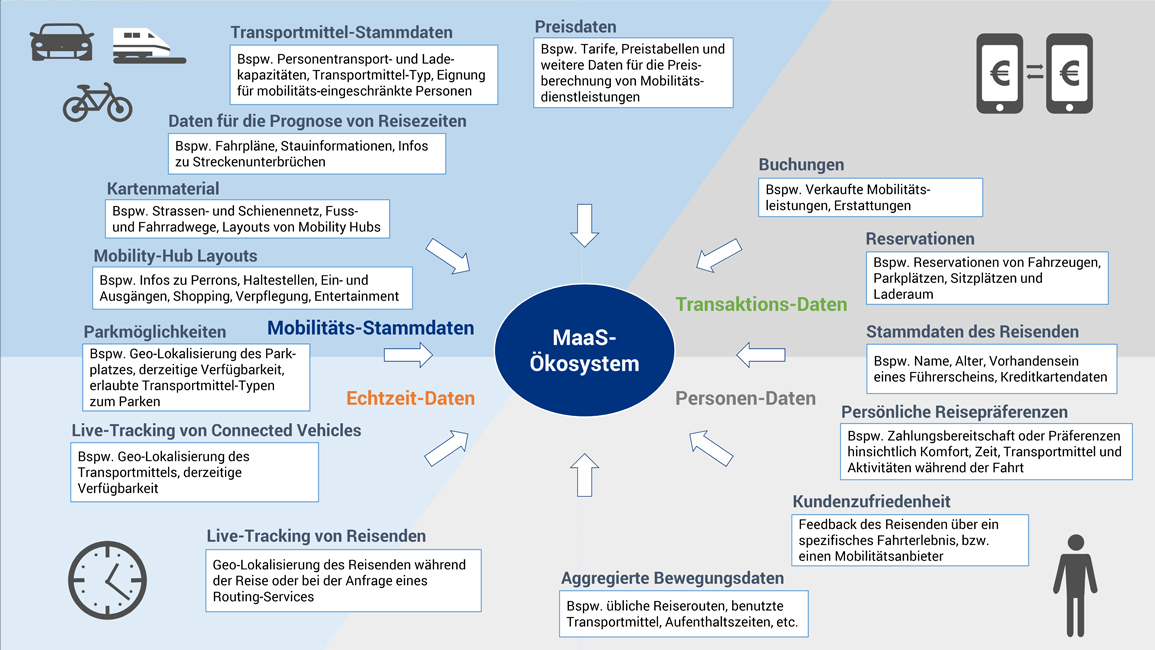

Cooperation is already a common practice in the mobility sector today, of course. In public transportation in particular, coopetition is an established behavior pattern. If a MaaS ecosystem is to be truly effective, however, the collaboration must be expanded further – especially in the integration of public transportation, road traffic, and micro-mobility services. This readiness to cooperate becomes a truly concrete topic in relation to the sharing of data relevant for mobility. If we want to be able to offer seamless door-to-door mobility to today’s demanding travelers, huge quantities of information must flow “backstage” across traditional organizational boundaries, including, for example, data about the travelers themselves, the transportation infrastructure, mobility hubs, or transportation means. These flows of data represent the lifelines of a functioning MaaS ecosystem (s. Figure).

“Yes” to data sharing! But how?

Those who would dispute that data sharing is important for the evolution of the mobility system are few and far between. Yet finding practical ways to implement it into the real world presents a massive coordination challenge for the mobility sector. Issues that are critical for its success must be clarified so that “smart” and “seamless” can function at all. We have spoken to various players involved in this highly diversified ecosystem on this topic – focusing in particular on the GAS region and movement of persons (see the information box about the study for a list of participants). We would now like to present some of our findings from the study within the scope of a two-part mini-series:

Part 1: What MaaS use cases is the industry treating as a priority and what data must be shared for these cases?

Part 2: How open should the data sharing be, and how can it be encouraged with the help of technical, regulatory, and contractual framework conditions?

Three essential use cases for data sharing in the age of smart mobility

Data sharing is oriented to specific purposes. The experts we interviewed were of one mind on this point. Conclusions about the data that must be shared in a MaaS ecosystem cannot be drawn without the help of a clear understanding of the common goals pursued by the industry. In this sense, we intend to shine a spotlight on the priorities for data sharing from the perspectives of three key use cases that, according to our interviewees, are currently the subject of the sector’s scrutiny.

Use Case 1: combined route planning for public transportation and private transportation

Intermodal mobility is nothing new. Digital trip planners today are already successfully combining public transportation to near and far destinations into integrated offers. These systems run into a wall, however at the interface of public to private transportation. One door-to-door trip planner describes the smart linking of public transportation, automobile, and micro-mobility services as “expanded multimodality”. Estimates today indicate that a car is unused on average for more than 95% of its useful life (for example, see: The Economist, The Long and Winding Road for Driverless Cars, 2017; Donald Shoup, The High Cost of Free Parking, Updated Edition, 2011). One of the most commonly mentioned reasons for the interest in seamless integration of public and private transportation has therefore been the desire to turn the relinquishment of a private vehicle into a valid alternative for a major part of the population. This is especially relevant for the GAS region, where not having public mass transportation is unimaginable. Services limited to carsharing only will not be adequate to satisfy the requirements of future mobility. There are further apparent advantages:

- Improved management of disruptions through redirection of traffic flows to alternative transportation opportunities in real time

- General relief of the transportation infrastructure (also through redirection)

“Smart mobility should make more situational travel possible” – mobility platform operator

An important distinction here: We are speaking about generic route planning algorithms that do not take into account individual preference profiles of travelers. Even this “basic form” of door-to-door mobility can generate appreciable added value. For most people, the most important criteria for a satisfactory routing proposal are the same and are so simple: travel time and price. Nevertheless, there are more than enough demanding challenges relating to concept and realization in this basic form alone:

- How are equivalent travel proposals prioritized in an ecosystem with any number of possibilities?

- How can transitions at mobility hubs be secured as seamlessly and painlessly as possible?

- How can multiple other environmental factors that can have an (unpleasant) impact on travel (such as weather, mass events) be taken into account in the routing?

More intense data sharing for real-time data, mobility hubs, and transportation means

Many of the types of data required for door-to-door route planning are already publicly accessible. Examples include the rates for mobility services, timetables, and maps. In the course of our talks, on the other hand, three data sectors materialized for which data sharing still has plenty of room for expansion:

- Reliable real-time data about travelers, transportation means and parking facilities. We are talking here about geo-localization of a vehicle (car-/bikesharing, etc.), for example. This is a must for any practical integration of timetable-based services (such as bus or train) and on-demand mobility services in private transportation. These data are already being collected and used in part, but frequently only within isolated mobility services.

- Layouts of mobility hubs: These data as well are already available in large part, but are frequently not digitalized, structured, or retrievable from a central location. Particularly important in this contact is information about parking facilities in the environs of these hubs. This is absolutely a fundamental pillar for the transition from private to public transportation. The fact remains, however: many cities, even today, do not have digitalized registries of their parking spaces.

- Master data for transportation means: There are a number of questions that must be answered if suitable wheels are to be provided to a traveler (or group of travelers). What is the capacity (passengers/luggage) of a means of transportation? Is a driver’s license required for its operation? Can it be used by people whose mobility is restricted? These data are available in many cases – but aside from professionally operated fleets, they are rarely available in structured, digitally usable form (one fascinating project in this respect is the “Blockchain cardossier”. The aim is to make relevant vehicle lifecycle data digitally available with the aid of smart contracts).

Study: Smart Mobility – Data Strategies in the Mobility of the Future

This article is part of an international Detecon study on the subject of Smart Mobility which reveals more than 70 fascinating insights concerning data strategies in the mobility of the future. These insights have been consolidated into a number of comprehensive propositions. Taking these propositions as a starting point, we conducted more than 20 qualitative interviews with representatives from well-known companies operating throughout the GAS region: from carmakers and logistics to rail and intercity bus transportation to mobility service and infrastructure providers. In addition, we obtained a market opinion on the propositions from more than 300 surveyed mobility experts.

Here you can download the German-language discussion paper:

Smart Mobility - Data and Data Sharing as Enablers for Smart Ecosystems

Use Case 2: integrated sales system over the full length of the mobility chain

Door-to-door route planning is helpful. But if travelers, after choosing the desired route, have to use a number of apps to make the reservations, receive multiple invoices for the services that have been used, and cannot be absolutely sure that their “shared cars” will really be available at the destination train station, the gain in convenience will be modest. So what is needed is a one-stop shop for purchase, reservation, checking, and settlement of intermodal mobility services – in the form of smart contracts, for instance. Depending on the technical realization, this will require plenty of data sharing between mobility service providers.

Data sharing with kid gloves for service and customer data

In this use case, we are talking about a transaction-based ecosystem. The context for data sharing is fundamentally different from that of route planning, but is no less important. Data must not simply be made public persistently and in one direction as, for example, is the usual practice with timetable data. Instead, there must be a bi- or even multilateral sharing of data relevant for the services between the service providers involved in a specific trip chain. Otherwise, transactions cannot be successfully completed.

One key challenge here is the handling of sensitive customer data. How much must the individual mobility service providers in a trip chain know about the traveler so that he or she can be identified, authorized to use their services, and billed for the services? The devil here is in the details.

Use Case 3: “learning from the crowd” with the aid of movement data histories

How do travelers get from their home in the city to a train station, and what entrances do they use to enter the station? At what traffic hubs is there congestion at what times of the day, and why does it occur? Tricky questions that railroad companies and urban planners by their own admission cannot answer satisfactorily today. Greater insight would be useful for many different purposes: the optimization of mobility services, the targeted expansion of infrastructure, the identification of dangerous bottlenecks, or the clever placement of shopping and restaurant opportunities.

The mobility sector’s interest in aggregated movement data histories is correspondingly high. One important boundary: tracking and storing data about mobility behavior of individuals is a delicate issue in terms of privacy. Clear feedback from the interviews: aggregated data are absolutely sufficient to achieve significant advances in the mobility system and the adjacent infrastructure on the basis of facts.

Capture door-to-door mobility flows with journey trackers and data sharing

Substantial quantities of use data are already being collected in the mobility sector today – but frequently in isolation for specific transportation services. Movement data would become more valuable if they reflected the door-to-door travel behavior, including movements on foot. There are a number of methods that would enhance the quality of the available data in this respect. For example, journey tracking apps are already in use today for such purposes. One example of such an app is “SBB DailyTracks” from “MotionTag”. An alternative is the integration of the use data from various mobility providers by means of a practical data sharing approach.

“Things will become really exciting for urban planning when 24-hour images of mobility flows are available” – urban mobility service provider

Personalized route planning a will-o’-the-wisp?

Route planning based on personal preference profiles is a trendy use case in the age of seamless mobility. For most of the interviewed experts, however, this plays a subordinate role (for the foreseeable future, anyway). For one thing, there are matters of far greater importance for an effective door-to-door trip experience, as described above. In addition, the practicality of a customized trip planner is fundamentally open to question. The sticking point: the mobility requirements for one and the same person often vary tremendously from one trip to the next. They change, for example, depending on whether the person is carrying luggage, just wants to arrive at the destination quickly, or wants to sleep or work during the trip. A route planner must consequently know all the general conditions for the next trip, not just the static preferences. The most likely result of such an endeavor: highly comprehensive profiling effort by travelers, a massive expansion of complexity in the routing algorithms, and a sobering lack of substantial added value for the customers.

Rudimentary forms can nevertheless be useful. For instance, mobility services can be filtered on the basis of fixed, personal characteristics such as mobility restrictions or the lack of a driver’s license.

To be continued ...

In this part of our mini-series, we have presented some key use cases for data sharing in the MaaS age and have examined the question of what data must be shared for this purpose. This helps to establish a rough framework for the acute data sharing requirements of the mobility sector. A fundamental part of the challenge for the industry, however, is in the practical implementation and encouragement of this data sharing. In the next part, we will present five issues closely related to practice for the successful implementation of data sharing in a MaaS ecosystem. Moreover, we will look into the issue of the extent to which common mobility platforms can assume a key role for this data sharing.