While long-term success is certainly desirable, it comes with its own risks. Successful companies often overlook the signs of the times and cling to the tried and tested while the world has long since moved on. Why fix something if it is not broken? Ambidexterity tries to wrest something positive from this culture of complacency and reconcile innovation and “business as usual,” creating a strong and efficient core business that promotes new business fields and innovative products.

Annual sales of almost $20 billion, technology pioneer, marketing trailblazer, monopoly position in the photographic film market — Kodak was the Google of its time. Twenty years later, Kodak was suddenly tottering on the brink of the economic abyss and filed for bankruptcy in 2012. What went wrong?

The beginning of the end

The advent of the digital camera sounded the death knell for analog photography, which became obsolete within the space of only a few short years. To be sure, Kodak recognized the market trend early on and responded with its first digital camera, but still failed to keep pace with the market. The company’s product was fine, but its organization — i.e., the structure, processes, culture, and mindset of the employees — was unable to keep up with the changes. In short: Kodak was caught in the competence trap. The tried and proven business model, the highly robust structures, and the established competencies — all of this wielded an almost hypnotic power, even on Kodak’s top management. “Skim off the cream” became the motto. Exploitation — i.e., improving the efficiency of the operating business at any cost — became top priority. What was lacking was the delight in exploration, an open mind for new ideas, a sense of the significance of transformation, and awareness of the urgent need of this transformation, even when success is at its peak — precisely at that point, in fact, whenever there is any doubt.

Kodak was not alone in confronting this challenge at that time, the gold rush years of digitalization; whether Nokia, Blackberry, Blockbuster, or Yahoo! — all of them had once been market leaders in their field. And they all missed out on crucial market developments by clinging to their firm belief in their core business.

But what is to be done when faced with disruptive technologies and business models? Is the next Kodak case only a matter of time?

Everything a question of balance

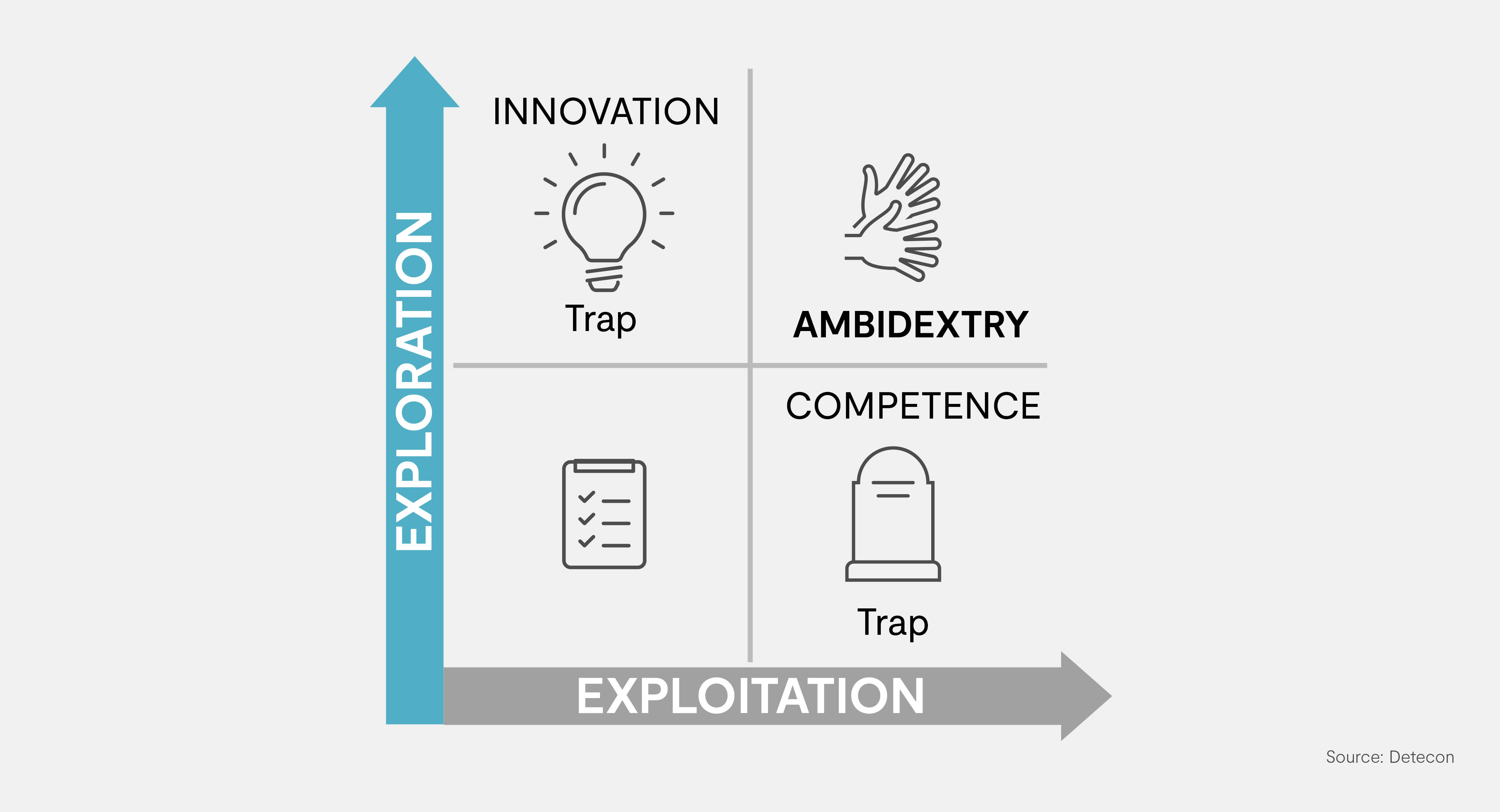

The concept of ambidexterity offers a way out of the competence trap. In its medical sense, ambidexterity means the ability to use either hand equally well; in the business world, it describes companies with these capabilities:

- On the one hand, they are able to use existing resources to maximize the core business and secure liquidity (“exploit”); and

- On the other hand, they strive to develop new knowledge and expertise that will drive forward innovative business models (“explore”).

Put simply, ambidexterity stands for a productive compromise uniting the traditional and the new. Finding the right balance between the present and the future is crucial. If a company focuses solely on future topics and neglects the factors that lay the essential economic foundation for such ambitions, problems are also foreseeable: the so-called innovation trap. The impressive story of the Japanese company Fujifilm is an excellent example of such ambidextrous balance.

Escaping the competence trap

After years of a wallflower existence in the shadow of Kodak’s dizzying sales figures, Fujifilm emerged in a position of strength from the radical market changes after the turn of the millennium. Why? Because it found the right balance between exploitation and exploration.

Just like Kodak, Fujifilm recognized at an early stage that the market was changing dramatically, but the enterprise’s decisions took a different direction. Although the Japanese remained loyal to their existing business model, they also invested in new technologies and business fields. The management at Fujifilm did exactly what decision-makers at Kodak failed to carry out. They had the courage to question their own business model while at the same time looking ahead into the future. They sought the answers to three elementary questions:

- How can we draw on our existing skills and expertise to tap successfully into new market segments?

- To what extent is it possible to revitalize our traditional business model and adapt it to changing market requirements by adapting and continuing to develop our core competencies?

- What strategies will enable us to address completely new markets by developing or acquiring innovative capabilities that go beyond our current business model?

The fundamental mindset is revealed in a quote from a Fujifilm manager: “As the print market changed and the film market continued to disintegrate, we had to reorient our business.” (Digital Imaging Reporter, 2012) If the environment changes, companies have no choice but to adjust accordingly.

Fujifilm seized the opportunities offered by the radical change in the photography market to redefine its identity and working methods and to rethink its products, services and the realization of its vision. Corporate management saw that the focus on photographic printing and low-end digital cameras promised little profitability in the long run and that the company’s future was in the production of chemical products and therefore in the health care sector. In contrast to Kodak, Fujifilm mined existing potential to diversify its operations further and to strike a balance between core business and new markets. While Fujifilm, with the aid of ambidexterity, impressively mastered the leap into the digital age, Kodak must accept the criticism that it acted too late or did not act rigorously enough.

All in all, the story of Eastman Kodak and Fujifilm reads like a lesson in the importance of ambidexterity in ensuring the future viability of companies:

- Organizations that are too sure of themselves and do not question their business models in the face of rapid change are playing Russian roulette with their own existence.

- New business potential must be developed in harmony with the maintenance of the core business.

- A mindset, demonstrated at the top management level, that makes the necessary comprehensive transformation in the company possible in the first place is indispensable.

This is truer than ever today as the fourth wave of digitalization, characterized by the widespread use of artificial intelligence and its potential for automating tasks and processes, breaks over us.

The responsibility of executives

Ambidexterity means that a company is capable of breaking new ground while turning existing strengths to its own advantage. The two-track approach heightens demands on management. Top executives and managers must encourage employees to develop new ideas and take risks, yet also ensure the stability and success of the company across all organizational units. Ambidextrous, two-pronged leadership is able to handle the resulting tension and the associated uncertainties between exploitation and exploration and use them productively for the benefit of the company.

How consistently such a management style is practiced often depends on the personalities. Not all managers are equally concerned about change management or enabling innovation. Some see their strengths more in consolidating familiar paths. Even if managers take both aspects of ambidextrous behavior into account in their day-to-day work, they usually do not do so equally. A balance between the two poles is required. With the right support, managers can learn how to become aware of the duality and ensure that ambidexterity is clearly visible in their own purview and realized in daily practice. There are possible consequences, however; management style, managers’ working methods, and indeed even the cooperation structures within the team may have to change.

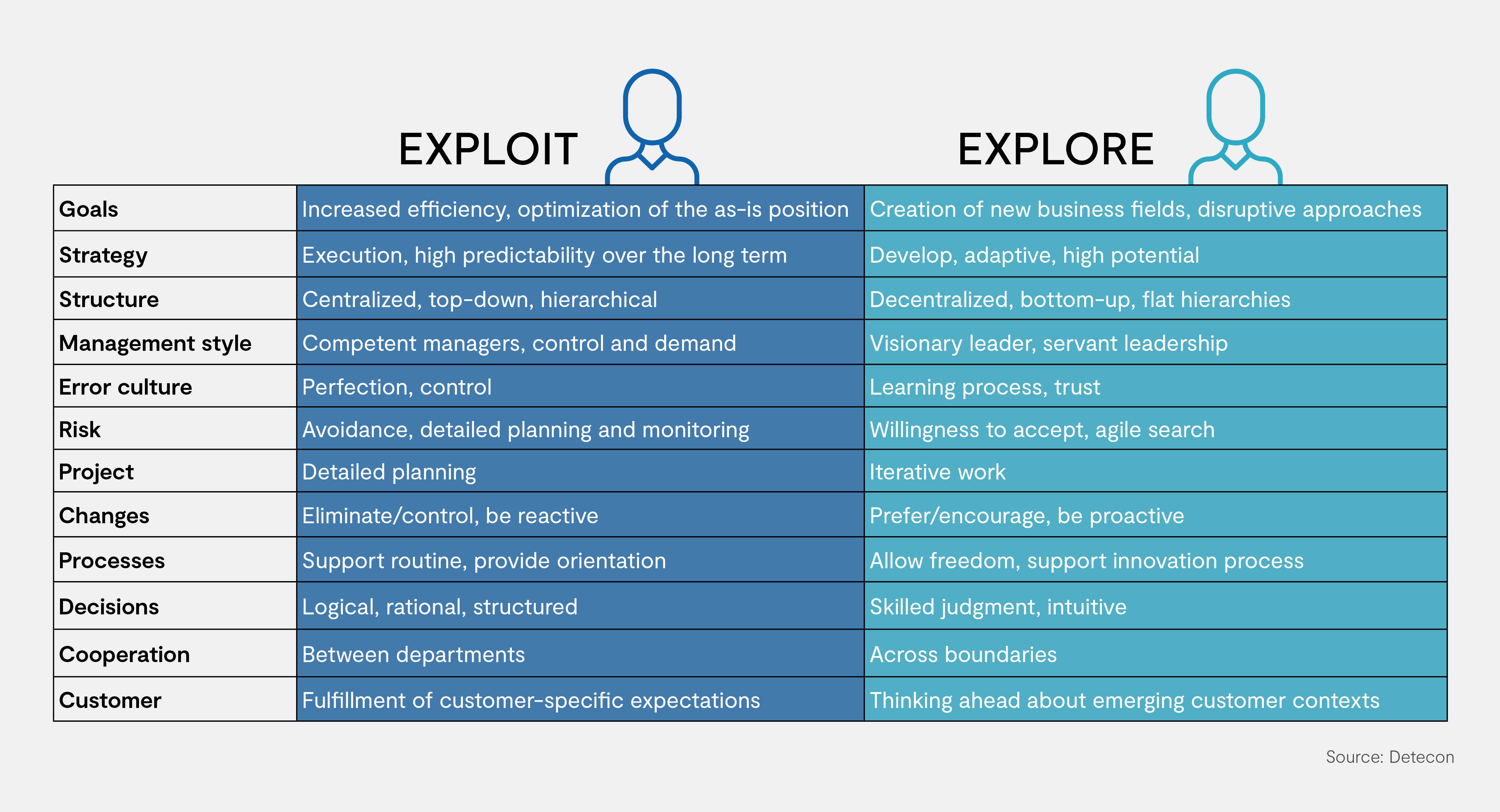

On the path to ambidextrous leadership

The implementation of ambidexterity can be analyzed and carried out according to different criteria; characteristics of each can be found in the “Explore” and “Exploit” ranges (see Figure 2). A look at the error culture, for example, clearly reveals the differences between the two extremes: in an “Exploit” environment, the focus is primarily on perfection and control — the avoidance of errors. In the “Explore” environment, mistakes are accepted as part of the learning process and the trust employees enjoy from the outset is enormous. Ambidexterity means being able to switch flexibly between the two extremes in the right environments and to decide what characteristic is best suited for the specific circumstances.

Sources: O’Reilly & Tushman (2016). Lead and Disrupt: How to Solve the Innovator's Dilemma